“We were remarking only a few months since that the most popular living novelists, in the strictest sense of that term, were women; that the fictions of American females had attained a wider circulation than those of either sex of any other nation. The author of Ida May strengthens that supremacy, for it is admitted by the publishers that this is her first book, and that she is a recruit to the already strong array of talented women engaged among us in writing fiction. Why her name is longer suppressed we can only conjecture. It is probable that her relations with the South are of such a nature as to indispose her to any more personal notoriety than is inevitable.”

IDa May

163 years after it sold out its first edition, Ida May came back in print June 2017.

Ida May is Twelve Years a Slave told from the point of view of a five-year-old white girl. In this antislavery romance novel/white slave propaganda, the child Ida May is kidnapped, beaten to the point of forgetting her own name, and sold into slavery. This book tells the story of her enslavement, her recognition eight years later, the black women who sustain her, and the young man who redeems her from slavery and later becomes her husband.

How popular was Ida May, in its time?

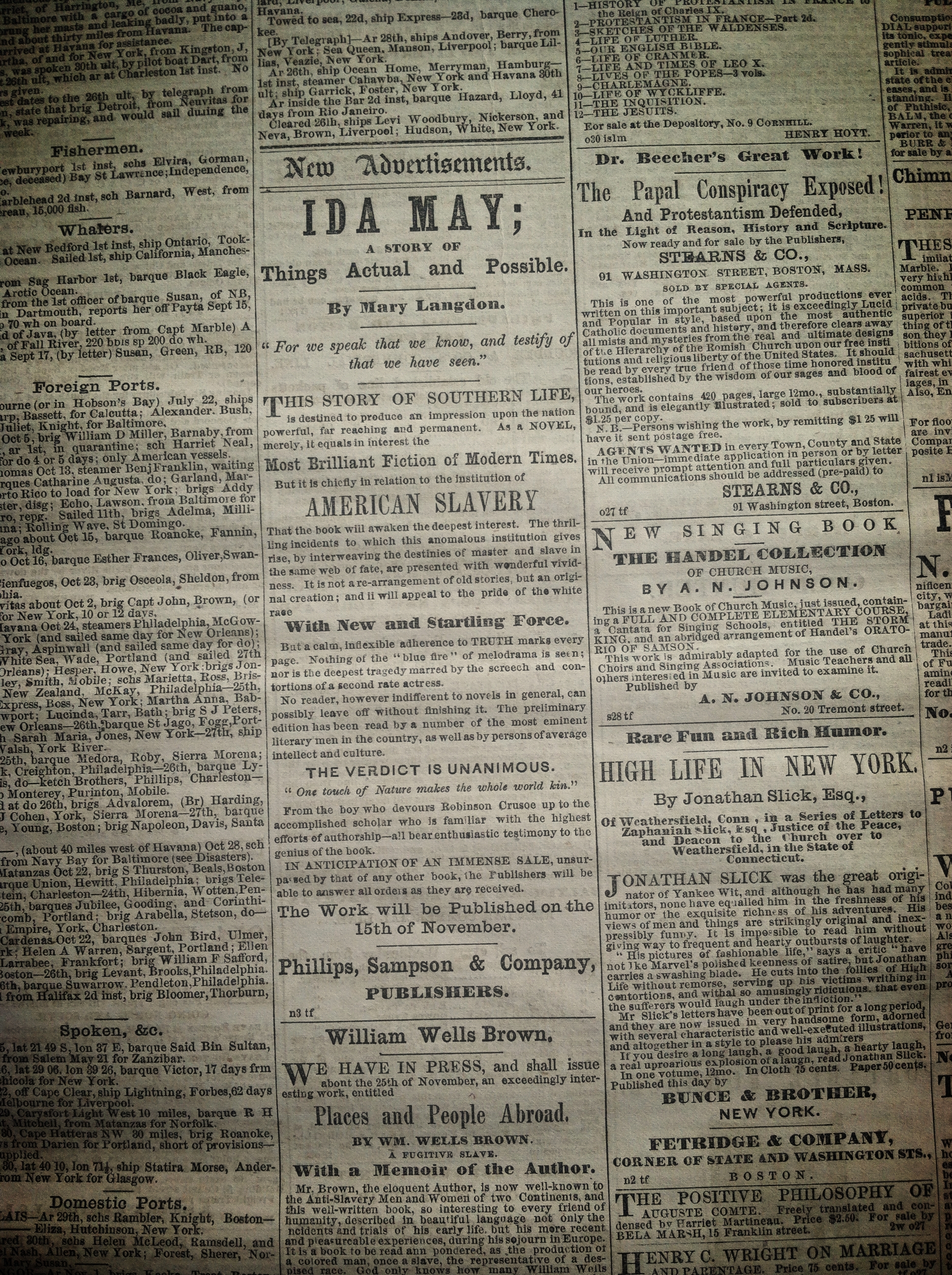

Widely considered to be the successor to the enormously influential Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Pike’s Ida May was an immediate success, selling 10,500 copies on the first day, 11,500 by the end of the week, and 60,000 copies by the end of the season. A celebratory review of Ida May published in Boston Evening Telegraph and reprinted in Frederick Douglass’s Paper, considered this book capable of bringing a generation of readers to anti-slavery in a national “moment of clarification or illumination”: “We believe that IDA MAY is but one of a series of books which will successively electrify the reading public, and quicken the impulses of all right-thinking men and women.”

So many orders flooded in for Ida May that the printers could not keep up with demand. The book’s release had to be delayed, twice, until it finally hit bookstores on Thanksgiving, 1854. Pike’s book outpaced every other book that Christmas—even an autobiography by circus man P.T. Barnum. The year that Ida May sold 60,000 copies, Charles Dickens serially published Hard Times in his magazine Household Words. He had sold only 70,000 copies by the end of the run. The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s biggest hit, sold out its initial print run of 2,500 copies in 10 days. Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave sold 27,000 copies in its first year. During his lifetime, Herman Melville sold 35,000 copies of his novels, all together.

The New York Evening Post, under its celebrated editor William Cullen Bryant, received an advance copy of Ida May from Bryant’s friend, publisher and marketing genius J. C. Derby (who also published Twelve Years A Slave). The Evening Post presented—on the front page—four columns of extracts from Ida May and an early review in its November 11, 1854 issue. Bryant made a strong initial claim that the author of Ida May was Harriet Beecher Stowe, saying, “No other living author could have written it.” Days later, the publisher Phillips, Sampson, and Company wrote to the paper, thanking them for compliment, but “Ida May is the production of an author as yet unknown to fame.” The Post retracted, but the debut made Ida May newsworthy, and the hunt for its author continued. They had puffed Ida May onto the bestseller list.

from the PREFACE

This story, which embodies ideas and impressions received by the writer during a residence in the South, is given to the public, in the belief that it will be recognized and accepted as a true picture of that phase of social life which it represents.

In the various combinations of society existing in the slave States, there may be brighter, and there certainly are darker scenes, than any here depicted; but I have preferred to take the medium tones most commonly met with, and have earnestly endeavored to

“nothing exaggerate,

Nor set down aught in malice.”

I have not written in vain, if the thoughts suggested by the perusal of this book shall arouse in any heart a more intense love of freedom, or bring from any lip a more firm protest against the extension of that system which, alike for master and servant, poisons the springs of life, subverts the noblest instincts of hu- manity, and, even in the most favorable circumstances, entails an amount of moral and physical injury to which no language can do justice.

M.L.

FROM CHaPTER TWO: the Kidnapping

But the child, the little one over whom that mother’s heart had yearned with inexpressible tenderness, the child who had been borne sleeping to the silent room, and laid on the bed beside the dying, that her hands might, till the last moment, retain their hold of her dearest treasures; how sad was her waking from that sleep beside the dead! how pitiful the wailing cry of childhood, “O, my mother! Give me back my mother!” Sadder still, and more touching, if possible, was her endeavor at self-control, when she became sensible that her paroxysms of grief added to her father’s distress, and her efforts to amuse him, wiping with her small, soft hand the tears from his eyes, and striving to amuse him with the playthings of which she took no notice at any other time. How often, in the deep and terrible trouble which afterwards befell him, did that desolate father recall these winsome acts, and the musical tones of her voice, and wonder that he should have esteemed himself so forlorn while he held that treasure to his heart!

For, one day—it was her fifth birthday—three or four months after her mother’s death, little Ida and her nurse walked out to gather flowers that grew along the side of a lonely road, which led through a piece of woodland, not far from the house. It was one of those glorious days in June, that make poets overflow with inspiration, and awaken the dormant organ of ideality in the most prosaic; and the clear air, the sunshine shimmering through green branches, and the melody of birds that rang through the woods, tempted them to prolong their walk till they reached the top of a hill, up which, after the fashion of our ancestors, the road had been made to ascend. This had once been the mail route from Philadelphia, westward, but a more direct and less hilly one having been constructed, the old road was left to solitude, except for the occasional passing of the farmers’ carts, and the loitering carriages of the few pleasure-seeking travelers, who preferred it on account of the picturesque scenery through which it wound. Having ascended the hill, Ida seated herself to rest on a fallen tree that lay along a bank by the roadside, and Bessy, the maid, who had gathered her apron full of flowers, sat down beside her to weave them into a wreath with which to ornament her straw hat. as they were thus occupied, a closed carriage, drawn by two horses, came slowly up the hill, followed by two men, who sauntered along as if enjoying the beauty of the hour and the scene. When nearly opposite the fallen tree, the horses stopped of themselves, as if waiting for their driver, who, with his companion, soon came up with them. When they saw the two children—for Bessy, a maiden of fifteen, was small of her age, and looked much younger—they paused, and, after looking at them a moment, said a few words to each other, and then one of them got into the carriage and took the reins, while the other approached the place where they were sitting. Bessy was accus- tomed to having strangers compliment the beauty of her little charge, and never had she looked so beautiful as now. She had taken off her hat, and her long dark curls were hanging carelessly down her cheeks, and over her neck, twined with a long spray of delicate pink flowers, with which she had ornamented herself. The mourning-dress showed her clear, dark complexion to great advantage; her cheeks and lips were like blushing rosebuds, and her brilliant eyes were lighted with merriment. Seen in the softened light of her leafy resting-place, with the deep shade of the forest for a background, she formed a picture on which a painter’s eye would have rested with untold delight. But other thoughts were in the mind of the dark-browed man who now ap- proached them. Standing beside Ida, he twined her curls around his fingers, and asked her a few questions, such as are usually addressed to a pretty child, seen for the first time, to which she replied fearlessly. at length turning partly away, as if to regain his carriage, the stranger stopped suddenly, and said to Bessy, “I find I’ve dropped my whip, walking up—there ’t is, lying in the road,” he added, pointing to something on the ground, about halfway down the hill—“come now, you’re younger ’n I am; s’pose you run down and get it, that’s a good girl, and I’ll stay with the little girl until you come back.”

Bessy hesitated a moment, not that she thought of danger, but she feared the child might not like to be left alone with a stranger. “Will you stay here while I go get the man’s whip?” she asked Ida.

The child turned her eyes earnestly upon him for an instant, and then, unwilling to own any fear, but yet detecting, with a child’s instinct, something sinister in the gaze that was fixed upon her, she rose from her seat, and said simply, “I will go with you.”

“O, no!” replied Bessy; “you can’t run quick enough, without getting tired, and there’s no good place there to sit and rest, as there is here. I won’t be gone but a minute.”

“Well,” said the child, reseating herself with a dignified air which she sometimes assumed, and which was amusing in one so young—“the man may go get into his carriage, and I’ll stay here alone and see you go.”

The stranger laughed, and took a few steps forward, and Bessy ran down the hill; but when she arrived at the object pointed out, she found it only a dry stick, and was turning to go back, when a shriek struck her ear, and she saw the child struggling in the arms of the stranger, who put her into the carriage, jumped in after her, and immediately the horses dashed away out of sight. Fear lent her wings; but when she reached the spot whence they had started, they were in the valley below, and galloping at a pace that made pursuit hopeless. Still she ran after them, filled with terror and anguish for the loss of the child, and yet hoping it might be that the men were playing some rude joke to frighten them both, and expecting every minute to see the carriage stop, and allow her to take her little charge. But no; it kept on and on, never slackening its speed, and the poor girl followed, calling wildly, and entreating the pity of those pitiless ones who were far beyond the reach of her voice. So long as the carriage remained in sight, although far distant, she had still a little hope; and when now and then she paused for an instant, to take breath, she heard, or fancied she heard, the piercing cries of the poor child, and the sound stimulated her to almost superhuman exertions; so that, when at length a turn of the road hid it from her eyes, and she fell down on the ground, almost dead with exhaustion, she was more than two miles from home.

FROM CHAPTER THREE: IDA's CApTORS

For a few moments after Ida’s capture, she continued to scream violently, partly from fright and partly from anger at the rudeness to which she had been subjected, for she had no definite idea respecting the cause or duration of her forced drive in that closely-shut carriage. But when her companion, shaking her violently, told her to be still or he would kill her, and enforced his words by a tingling blow on her cheek, all other feelings, even the sense of pain, were lost in the extremity of terror, and she shrank away from him and sat silent and motionless, save for the stifled sobs that swelled her bosom. yet, as the swift motion continued, and she became sensible that she was being borne rapidly away from home and all she loved, she ventured timidly to ask her companion why he had taken her, and where she was going.

“O, I’m only going to take you to ride a little way,” he replied. “you be a good girl and keep still, and we’ll see lots of pretty things.”

“What made you strike me so hard for, then?” said the child; “and why didn’t you let Bessy come? I don’t want to go without Bessy.”

“O, Bessy’ll come by and by; and if you are good, I’ll give you candy.”

“I don’t want candy, and I do want Bessy. O Bessy! Bessy! come and take me!” she cried, piteously.

“Come, now, hush!” said the man. “What are you afraid of? I’ll carry you back. Hush, I tell you! I’ll be good to you, if you won’t cry. I’m a first-rate fellow to good little girls, and they all like me. Come, stop crying and give us a kiss. you’re a mighty pretty little girl.” and, as he spoke, he drew her toward him with an ill-feigned show of tenderness, and attempted to kiss her.

But the child indignantly resisted him. “Get away, you bad man!” she said; “you shan’t kiss me. you have no right to take me away from papa and Bessy, and I will cry till I make you carry me home again;” and she burst into wild screams, which could hardly be stilled, even for a moment, by the fierce threats and repeated blows that were administered. at length, as they slackened their pace somewhat, in ascending a hill, the driver

opened a small window in the screen behind him, that closed the front of the carriage, and said, shaking his fist at her as he spoke, “I see something coming up over the top o’ the hill, and if you don’t stop that young ’un yelling, the fat’ll be all in the fire. I say, Kelly, stop her.”

“I’ll fix her, Bill,” was the reply; and, taking a thick woolen scarf from under the seat, he suddenly threw it over her head and around her mouth, in such a way as completely to smother her cries, and almost to stop respiration. Thus they continued for some miles; and when it was removed, the poor child, overcome by fright and suffering, dared make no further resistance, but wept silently, and at last fell into an uneasy sleep. When she awoke, it was nearly dark, and as soon as she opened her eyes, Kelly ordered the carriage to stop; and, taking a little cup and phial from his pocket, he poured out a spoonful of dark liquid, which he diluted with water from the large bottle beside him, and then put the cup to her lips. It was very bitter, and, after the first swallow, she drew back. “drink it!” said he, raising his hand as if to strike her; and she complied instantly.

“There, now, that’s a good girl,” said he; “you shall have some candy.” and, as he spoke, he offered her a little piece.

“I don’t want the candy, but I’m very thirsty—will you give me some water?”

“O, yes,” replied Kelly; and, as she drank it, he added, “you are a little fool not to like candy. you’ll have bitter enough in this world, I’m thinking, and you’d better take all the sweet you can get.”

“Why will I have bitter enough?” said Ida, timidly. “What are you going to do with me?”

“you’ll find that out soon enough,” replied her companion, with a sardonic laugh; “you needn’t be in any hurry. Little girls hadn’t ought to ask questions;—haven’t you been told that?”

Thus repulsed, the child sank back into her corner, and said nothing more, and soon, yielding to the influence of the powerful soporific she had taken, she fell into a deep slumber. Thus it was that, stretched lifelessly on the seat of the carriage, with her senses fast locked in oblivion, she knew nothing of their stopping at the hotel to have the horses changed, and made no sound by which she could have been discovered. The days that followed, during that painful journey, were but a repetition of the first, except that her attempts at resistance became fewer as she yielded more and more to the influence of fatigue, and fear, and suffering.